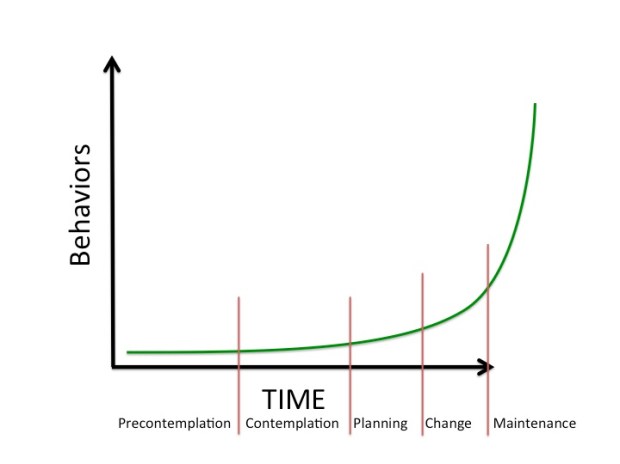

In 1983, Prochaska & DiClemente theorized that there was process of making behavioral change. This five step model was developed while evaluating how people changed from unhealthy to healthy behavior. This was primarily focused on items such as making choices of exercising and eating healthy. From a safety standpoint, there are many similarities in how behavioral change is made. It is not the 8+ hours a day that people spend in the workplace that overall determines their health and safety. It is dependent on many factors including good systems and behaviors. There are many similarities between wellness and HSE processes. The most obvious is the “H” for health. HSE is about health and choices and behaviors that come with a healthy approach to the workplace and risk. So in that spirit of the theory, this seems to apply very well.

Stage 1: Precontemplation (Subconsciousness)

The model consists of four “core constructs”: “stages of change,” “processes of change,” “decisional balance,” and “self-efficacy.”People at this stage do not intend to start the healthy behavior in the near future (within 6 months), and may be unaware of the need to change. People here learn more about healthy behavior: they are encouraged to think about the pros of changing their behavior and to feel emotions about the effects of their negative behavior on others.

Precontemplators typically underestimate the pros of changing, overestimate the cons, and often are not aware of making such mistakes.

One of the most effective steps that others can help with at this stage is to encourage them to become more mindful of their decision making and more conscious of the multiple benefits of changing an unhealthy behavior.

Stage 2: Contemplation (consciousness)

At this stage, participants are intending to start the healthy behavior within the next 6 months. While they are usually now more aware of the pros of changing, their cons are about equal to their Pros. This ambivalence about changing can cause them to keep putting off taking action.People here learn about the kind of person they could be if they changed their behavior and learn more from people who behave in healthy ways.

Others can influence and help effectively at this stage by encouraging them to work at reducing the cons of changing their behavior.

Stage 3: Preparation (pre action)

People at this stage are ready to start taking action within the next 30 days. They take small steps that they believe can help them make the healthy behavior a part of their lives. For example, they tell their friends and family that they want to change their behavior.People in this stage should be encouraged to seek support from friends they trust, tell people about their plan to change the way they act, and think about how they would feel if they behaved in a healthier way. Their number one concern is: when they act, will they fail? They learn that the better prepared they are, the more likely they are to keep progressing.

Stage 4: Action(current ‘action)’

People at this stage have changed their behavior within the last 6 months and need to work hard to keep moving ahead. These participants need to learn how to strengthen their commitments to change and to fight urges to slip back.People in this stage progress by being taught techniques for keeping up their commitments such as substituting activities related to the unhealthy behavior with positive ones, rewarding themselves for taking steps toward changing, and avoiding people and situations that tempt them to behave in unhealthy ways.

Stage 5: Maintenance(monitoring)

People at this stage changed their behavior more than 6 months ago. It is important for people in this stage to be aware of situations that may tempt them to slip back into doing the unhealthy behavior—particularly stressful situations.It is recommended that people in this stage seek support from and talk with people whom they trust, spend time with people who behave in healthy ways, and remember to engage in healthy activities to cope with stress instead of relying on unhealthy behavior.

The reason I found this theory so interesting is that there is still a belief that culture and behavior can be created quickly. Each organization, and in such, each individual have to go through this process of creating new and positive behaviors. There is nothing about these steps that can be rushed or completed without due time or in their respective order.

So far in my career, I have been part of organizations that are undergoing cultural change because of:

- 2x = Downsizing

- 1x = Startup

- 1x = Expansion

- 3x = Safety program turnaround

- 1x = Less than 6 month poor culture

- 2x = Greater than 5 year poor culture

I have seen a trend of how these work. The first six months to one year, the company is patient. They let the work happen and focus on the process and not as much on the results. Then, they get impatient for results. Just like a quality or production problem, they want to see results and now! When we look at the model above, three of the five behavioral processes are all about mindset and preparing for the change. The forth item is where the change actually occurred, and the last is maintaining and improving on the behaviors and culture that has been created.

It is my experience behavioral and cultural change is exponential. It takes time for the processes to work and help people internalize that change. Assuming that each of four phases are equal in time it takes to implement (removing maintenance as that is a termination step). It takes 75% of the time to prepare for the change and 25% of the time to make the change. This analysis supports the exponential idea of the process. The best outcomes that I have seen is that for each year a behavior or culture is not nurtured, it takes 50-75% of that time to create a positive culture. For example, a site that has not had a robust safety program for 10 years will most likely take 5-7 years to create the process and results of a good safety program once organization starts making the right changes.

Change takes time. Behaviors take even longer as there are complex emotions and cultures that have to be influenced. The next series of postings will focus on each of the five elements and how they can be applied to creating safety behavioral change.